About TSC

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex, abbreviated to ‘TSC’, is a rare genetic disorder. It is caused by mutations in the genes TSC1 or TSC2 that produces the proteins hamartin and tuberin respectively. TSC affects approximately 1 in 6000 individuals involving all racial and ethnic groups. That means that there are about 1-2 million people around the globe who have the disorder.

Mutations in TSC2 are more common and are usually associated with more severe manifestations than those in TSC1. People with TSC develop benign tumors (known as hamartomas) in multiple organ systems including the skin, the brain, the heart, the kidneys, the eyes and the lungs, but these manifestations can vary significantly between different people with the disorder. Some people can therefore have very few physical manifestations, while others have many or very severe physical manifestations.

More about TSC

About TAND

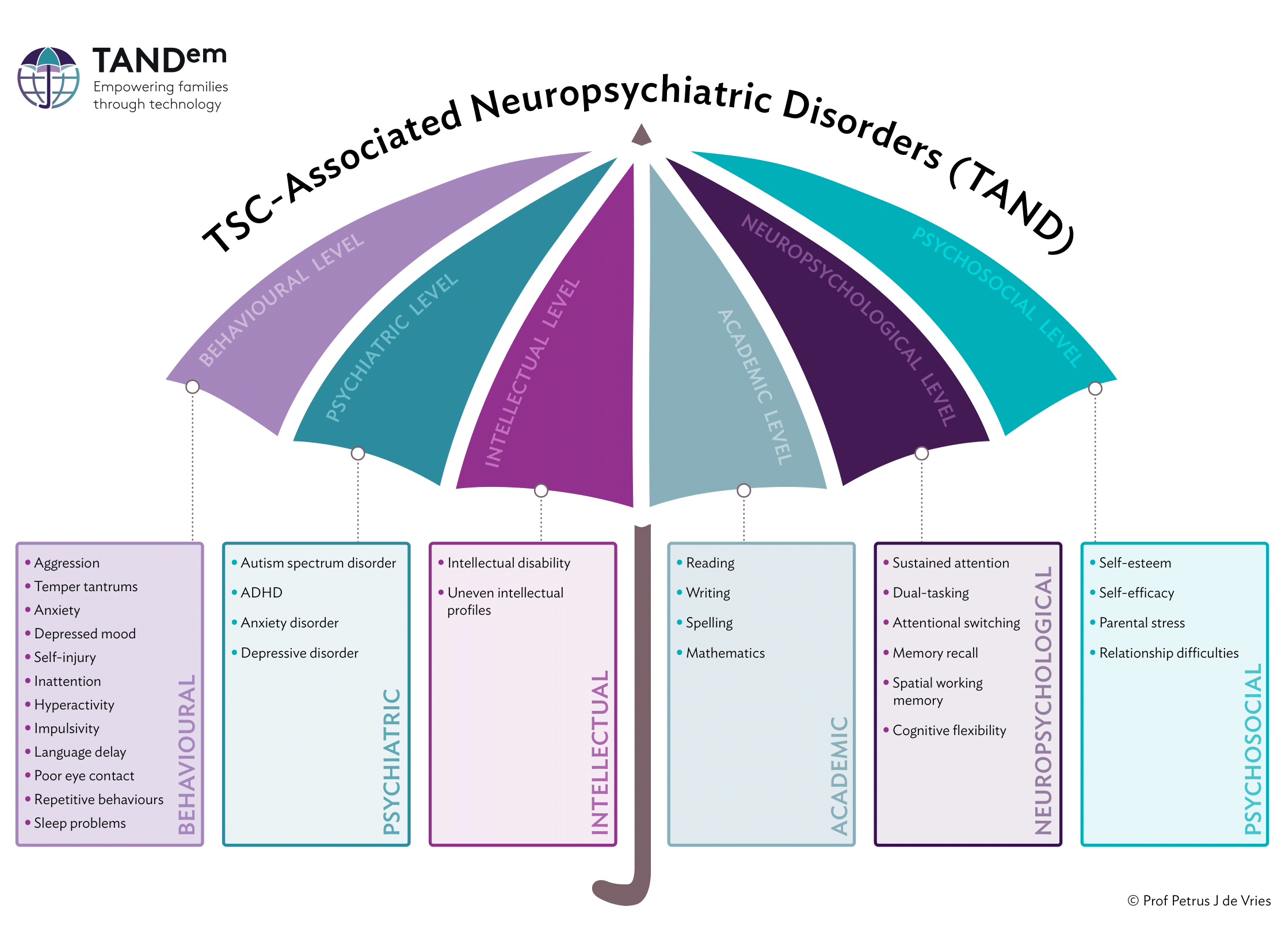

Apart from the physical manifestations of TSC, most individuals with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (about 90%) are affected by a broad range of behavioural, psychiatric, intellectual, academic, neuropsychological and psychosocial difficulties. Examples include autism, ADHD, intellectual disability, anxiety and depressive disorders, and difficulties in scholastic skills. These problems often cause the greatest burden to individuals with TSC and their families. Unfortunately, they are often not identified or treated.

The Neuropsychiatry Panel of the International TSC Consensus Conference in 2012 realised that there was a big gap in the identification and treatment of these difficulties. In order to reduce this ‘identification gap’ we created the term ‘TAND’, which stands for TSC-Associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders. The inspiration for the name came from the HIV community. In HIV clinical services doctors and nurses had become very good at identifying and treating the physical features of HIV. But, many people with HIV also had learning and mental health problems. The HIV community introduced the term HAND (HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders) as a strategy to increase awareness and action around HAND. We therefore decided to use a similar strategy for TSC. To generate a ‘shared language’ that might support international communication and to guide future research, we described six distinct levels of TAND, as shown in the umbrella figure.

More about TAND

Behavioural level

Behavioural problems in themselves do not constitute a psychiatric disorder, given that different elements need to be taken into account to determine whether or not behaviour is appropriate and what the reason is for a person’s behaviour. Temper tantrums in a two-year-old, for example, are appropriate to the developmental level of the child, and usually do not require additional supervision. The same behavior in a 15-year-old does request additional evaluation to understand what the reasons and triggers are. The behavioural level therefore often represents a reason for referral for additional evaluation by a doctor or other specialists.

More about behavioural level

Psychiatric level

At this level, the behaviour is evaluated in the context of a person’s general development and biological, psychological and social profile. When someone exhibits pronounced behavioural problems that persist over time and are a major source of stress or disability, a psychiatric disorder may be diagnosed, as defined in DSM-5 or ICD-11. The most common psychiatric disorders associated with TSC are autism (40 – 50%), ADHD (30 – 50%), and depressive and anxiety disorders (30 – 60%). Psychosis does not appear to be more common than in the general population and most psychotic symptoms in TSC are associated with seizures, especially those originating in the temporal lobe. Diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder is crucial as a stepping stone to appropriate parent/caregiver education and training, individual or other interventions, educational interventions or targeted support for employment.

More about psychiatric level

Intellectual level

About half of people with TSC have an intellectual disability, defined as an IQ score <70, ranging from mild to severe. The IQ profile is often discordant, with strongly fluctuating strengths and weaknesses, even in people with a normal IQ. The evaluation of intellectual capacities is essential for interpreting behavioral problems, but also for the search for optimal learning path counseling at school or work.

More about intellectual level

Academic level

The majority of school-aged children with TSC (even if they have normal intellectual abilities) have scholastic difficulties requiring further assessment and guidance. These children are often incorrectly labeled as “stubborn” or “lazy” and therefore may miss out on appropriate educational support.

More about academic level

Neuropsychological level

Neuropsychological assessments are used to map specific strengths and weaknesses of the various brain functions required for learning, thinking and behavioral regulation. On the one hand, these neuropsychological functions show a clear correlation with behavioral problems, psychiatric disorders, intellectual abilities and school functioning.

On the other hand, people with TSC can also show very specific neuropsychological deficits (score <Pc 5) such as, for example, difficulties in performing two tasks at the same time or problems with organization and planning, which can significantly interfere with day-to-day functioning.

More about neuropsychological level

Psychosocial level

At this level, important determinants of quality of life are mapped, such as selfimage, family functioning, parental stress, and relationship problems. This largely reflects the resilience or burden of care in a family. Although the psychosocial problems associated with TSC are often particularly serious, people with TSC and their families are rarely questioned by health care providers about these nonmedical aspects of the disease.

More about psychosocial level

How to evaluate the different levels of TAND

Behavioural level

All observed behaviours. Evaluation through direct observation by parents, family, teachers or caregivers, or using a range of questionnaires.

Psychiatric level

Defined by diagnostic classification systems such as DSM-5 or ICD-11. At this level, the clinician with training in mental health disorders determines whether behaviours observed at the behavioural level meet the criteria for specific psychiatric disorders.

Intellectual level

General level of intellectual development as measured by standardized IQ (intelligence quotient) measures, and by evaluation of adaptive behaviours in daily life.

Academic level

Refers to specific learning disorders such as defined by DSM-5 or ICD-11, such as reading, writing, spelling or mathematics disorders.

Neuropsychological level

Brain skills such as language, executive skills, memory and visuo-spatial skills, evaluated using standardized neuropsychological instruments.

The psychological and social impact of TSC on the individual with TSC, the family and their community. Psychosocial functioning can be measured by some specific rating scales and through asking people about this.

Behavioural level

All observed behaviours. Evaluation through direct observation by parents, family,teachers or caregivers, or using a range of questionnaires.

Psychiatric level

Defined by diagnostic classification systems such as DSM-5 or ICD-11. At this level, the clinician with training in mental health disorders determines whetherbehaviours observed at the behavioural level meet the criteria for specific psychiatric disorders.

Intellectual level

General level of intellectual development as measured by standardized IQ(intelligence quotient) measures, and by evaluation of adaptive behaviours in dailylife.

Academic level

Refers to specific learning disorders such as defined by DSM-5 or ICD-11, such as reading, writing, spelling or mathematics disorders.

Neuropsychological level

Brain skills such as language, executive skills, memory and visuo-spatial skills,evaluated using standardized neuropsychological instruments.

Psychosocial level

The psychological and social impact of TSC on the individual with TSC, the family and their community. Psychosocial functioning can be measured by some specific rating scales and through asking people about this.

Notes: ADHD: Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Edition (WHO, 2018).

About the TAND Checklist

After we created the term TAND, many people around the world asked if we could develop a checklist that could help clinical teams to screen for TAND in a systematic way. The Neuropsychiatry Group therefore designed the ‘TAND Checklist’.

The first TAND Checklist was developed to help doctors and other clinicians who work with people to have a conversation about TAND. It is called the Lifetime version of the TAND Checklist (or ‘TAND-L Checklist’). We recommended that all people with TSC should be screened for TAND at least once per year, and we suggested that the TAND Checklist could be a good tool to help with this screening.

INTRODUCTION TO TAND &

THE TAND CHECKLIST

About TANDem

TANDem in a Nutshell

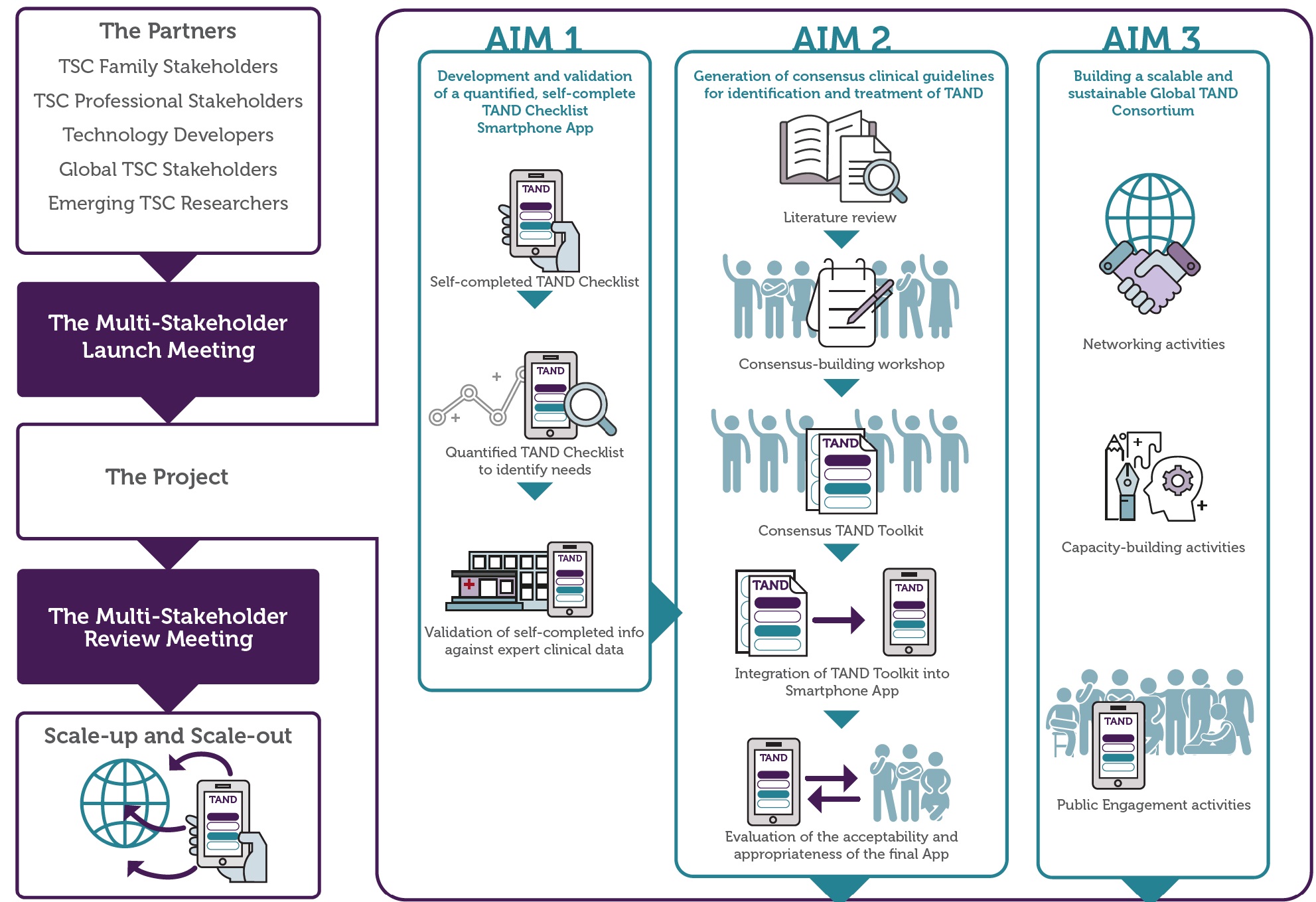

TSC-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) represent the number one concern to families around the globe, yet they are highly under-identified and under-treated – we refer to these as an ‘identification gap’ and a ‘treatment gap’. In 2012 we introduced the term ‘TAND’ and in 2015 we created the TAND Checklist to reduce the ‘identification gap’. Research using the TAND Checklist showed that we could identify seven natural TAND Clusters that may be useful to reduce both the identification and treatment gaps for TAND further.

Following our earlier research, community-based participatory research with families and a range of TSC stakeholders identified three next steps for action:

- Creation of a self-report and quantified version of the TAND Checklist

- Creation of a digital tool such as an app for the TAND Checklist

- Generation of evidence-based guidelines and a toolkit for next-step management of TAND Clusters

The TANDem project was a direct result of the feedback from our TSC stakeholders, and has three aims:

- AIM 1: Development and validation of a quantified, self-report TAND Checklist (TAND-SQ), built as a mobile app

- AIM 2: Generation of consensus clinical guidelines for identification and treatment of TAND Clusters, to be incorporated as a toolkit into the app

- AIM 3: Establishment of a global TAND Consortium through a range of networking, capacity-building and public engagement activities

Update on the TANDem project